It’s December! Chocolate-filled Advent calendars are in use in my house, and I’m scrambling to catch up after being gone the entire week of Thanksgiving. Naturally, my holiday decorations are not up–they’re not even down from the attic!–but I hope to remedy that this week, or this weekend at the the latest.

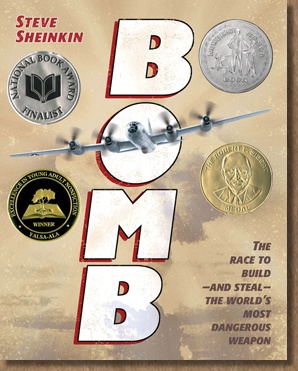

This month, I’m reviewing Bomb: The Race to Build-and Steal-the World’s Most Dangerous Weapon by Steve Sheinkin. I’ve had my eye on this one for a while, mostly for my boys, but eventually, I decided to break with personal tradition and read this middle-grade nonfiction book myself. I was not disappointed! This was one fascinating read, and I agree with the book’s School Library Journal review which raves that it “reads like an international spy thriller.”

This month, I’m reviewing Bomb: The Race to Build-and Steal-the World’s Most Dangerous Weapon by Steve Sheinkin. I’ve had my eye on this one for a while, mostly for my boys, but eventually, I decided to break with personal tradition and read this middle-grade nonfiction book myself. I was not disappointed! This was one fascinating read, and I agree with the book’s School Library Journal review which raves that it “reads like an international spy thriller.”

The blurb, from Amazon:

In December of 1938, a chemist in a German laboratory made a shocking discovery: When placed next to radioactive material, a Uranium atom split in two. That simple discovery launched a scientific race that spanned 3 continents. In Great Britain and the United States, Soviet spies worked their way into the scientific community; in Norway, a commando force slipped behind enemy lines to attack German heavy-water manufacturing; and deep in the desert, one brilliant group of scientists was hidden away at a remote site at Los Alamos. This is the story of the plotting, the risk-taking, the deceit, and genius that created the world’s most formidable weapon. This is the story of the atomic bomb.

The book was a 2012 National Book Awards finalist for Young People’s Literature, and a 2013 Newbery Honor book.

This book succeeds on many levels. First off, it covers a wide span of inter-related occurrences from 1938, through the end of the second world war in 1945, and even a bit afterwards, slotting them all together like puzzle pieces in this tangled, complex web of history. It’s fascinating to read about the birth of such a impactful idea and all of the individuals and events that contributed to its eventual success, as well as those that contributed to its theft. In all the stories about WWII heroism, the men and women of this tale are largely unsung. Whether or not you agree with the creation of the bomb–it is impossible not to respect the patriotic contributions of The Manhattan Project team of scientists who worked tirelessly towards success in order to bring about the end of the war.

Secondly, and most significant to me, Sheinkin humanizes all of it. The “characters” are presented with the fears, uncertainties, and misgivings of the project’s failure as well as its success, and thus, the book transcends a typical historical account to become a collective biography of those involved with the bomb. Even the spies are written sympathetically.

Finally, this book is very accessible. I honestly feel like I now know a good bit about the uranium, plutonium, and hydrogen bombs, all without subjecting myself to a dry historical text. There are only 236 pages in this book, and these pages have plenty of white space and lots of cliff-hangers. The story touches on lab discoveries, experimental trial and error, recruitment for The Manhattan Project, spy development, Presidential commentary, military perspective, and Soviet and Japanese bomb progress. And all of it is pretty riveting. You get caught up in the urgency the players in this story were feeling seventy plus years ago.

I would recommend this book to anyone interested in the history of the atomic/nuclear bomb, any WWII history buff, and anyone looking for a true-story action adventure.

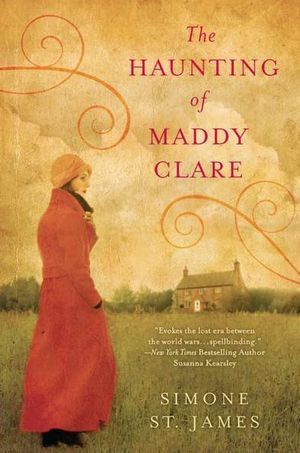

and added to the novel’s tension and uncertainty. The longterm effects of WWI further contributed to the stark loneliness of the setting, even though the war had ended several years prior. All of the characters were well-drawn and interesting, particularly Sarah Piper, whose courage in the face of terror, shock, grief, and even madness, was magnificent. And then there was the ghost of Maddy Clare.

and added to the novel’s tension and uncertainty. The longterm effects of WWI further contributed to the stark loneliness of the setting, even though the war had ended several years prior. All of the characters were well-drawn and interesting, particularly Sarah Piper, whose courage in the face of terror, shock, grief, and even madness, was magnificent. And then there was the ghost of Maddy Clare.